Have you ever woken in the middle of the night with a sore throat or an ear infection? You want to book the next available appointment with your local GP, but their reception doesn’t start taking calls until 8am. A common scenario.

In an increasingly digital world where convenience and accessibility are highly valued, patients are seeking digital solutions to find local healthcare providers and make appointment bookings. An online booking system may be the competitive advantage that your practice needs.

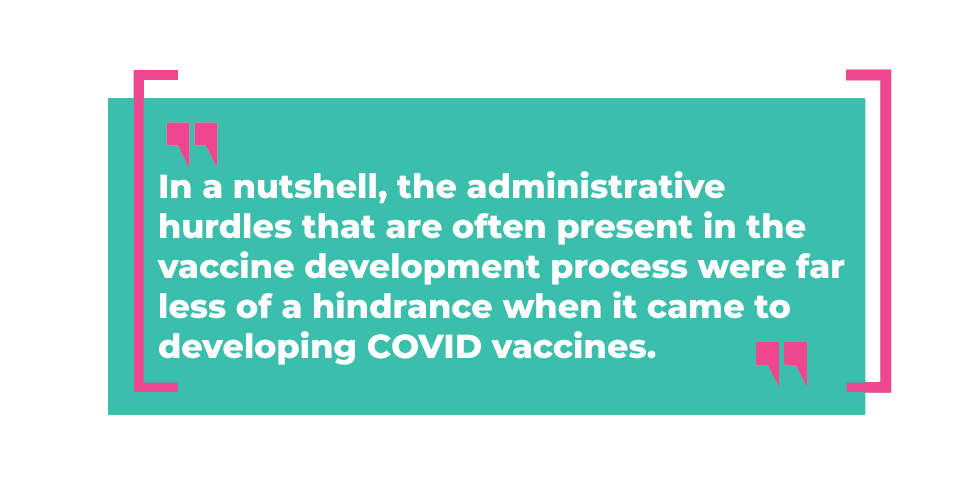

Prior to COVID-19, there was a general opinion that older generations may reject the idea of adapting to smart phone technology. Since COVID, most people have had no choice but to become familiar with QR code check-ins, online vaccine appointment bookings and telehealth appointments. Research undertaken by the Global Centre for Modern Aging in 2020 indicates that since COVID-19, 22% of Australian’s aged 60 and over have had an online consultation with a practitioner and 44% had a phone consult, with strong approval.

Some people expect a self-service option when booking their appointments across every industry, a sentiment shared particularly amongst the younger generation. If you are not providing online scheduling as an option, these patients are going to be more likely to switch to a practice that does.

Let’s explore 5 significant benefits that implementing an online booking solution may provide for your practice:

1. Convenience is KING

One of the main reasons people appreciate online booking systems is the 24/7 convenience and access to your practice. Being able to make bookings on the go and after-hours is a BIG bonus. It grants the flexibility and freedom for patients to book appointments at any time of the day or night. Gone are the days of listening to hold music and being told that you are the 4th caller in the queue. It also empowers patients to facilitate their own healthcare journey and reschedule their appointments when necessary.

2. Reduced Wait Times & No-Shows

For the majority of us that have come to expect service on demand, this is a hassle-free tool that simplifies the patient journey and closes the loop on patient scheduling. When patients are able to book appointments online, they can see the available appointment times of their preferred practitioner, and then choose the option that works best for them.

Automated appointment confirmations are a key feature that can significantly reduce the number of missed appointments – especially for those with busy lives or for the ones who just have a habit of forgetting important dates.

3. Improved Patient Satisfaction

Happy patients, happy practice. A patient’s experience is essential to a successful practice. Online scheduling makes it easier and more convenient for patients to manage their own appointments using the web and smart phones. In the 2021 CommBank GP Insights Report, it was stated that out of the 38% of people who manage appointments though apps or websites, 56% reported that these online booking platforms effectively enhanced their overall experience. Word of mouth is also important to consider, patients who have a positive and seamless experience with your practice are more likely to return and recommend your practice to their family and friends.

4. Better Resource Management

Introducing an online booking solution can free up your reception staff, allowing them to focus on the patients presenting in front of them. Improved resource allocation can enable admin staff to focus on more pertinent tasks, rather than answering inbound calls and sending out manual appointment confirmations and reminders. According to an article posted by the RACGP in 2022, 60% of practice owners reported working over 40 hours per week and experience significantly higher levels of discontent with their work hours. This is likely a strong contributing factor to 40% of practice owners who state they find difficulty sustaining a good work-life balance.

5. Superior Data Handling

Online systems eliminate the need for manual data entry and ensures that patient information is accurate and up to date. More importantly, online systems avoid awkward double-bookings, which usually means someone will end up waiting much longer than anticipated. This has the potential to delay the rest of your existing bookings for the day and inconvenience a lot of people that are short on time. However, awkward moments like this can soon be a thing of the past.

Is an online bookings platform the solution your practice needs? Convenience and accessibility reign supreme when cultivating a practice-patient relationship and online booking systems can significantly help improve overall patient satisfaction. Revising your scheduling system may enhance patient satisfaction, retention, and acquisition. It’s often the first interaction patients have with your practice and as we know, first impressions count.

Authored by:

Olivia Savage

Marketing & Communications Specialist

at Best Practice Software

Explore our range of news and training resources:

Bp Learning Video Library | Bp Learning Training Options | Bp Newsroom Blog

Subscribe to Our Newsletters | Bp Learning Webinars